How Corona SDK Shaped Mobile Game Development? A Retrospective

Corona SDK promises 10x faster app development, but was it truly a game-changer? Dive into its strengths, weaknesses, and whether it changed the world for the better?

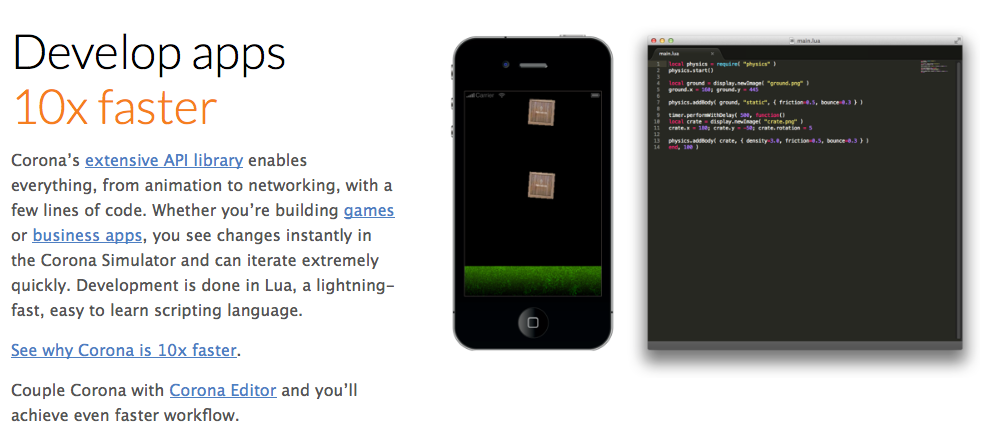

In the early 2010s, Corona SDK was one of the most talked-about tools for mobile game development. With success stories like Doodle Jump, The Secret of Grisly Manor, and The Lost City, it fueled the dream that indie developers could build the next big hit. Corona’s tagline at the time, “Develop apps 10x faster,” captured both the excitement and the skepticism around the platform.

What follows is a look back at Corona SDK during its most active years: the strengths that made it appealing, the weaknesses that slowed some projects down, and the marketing that raised more questions than answers. Afterward, we’ll explore what became of the technology.

Why Would Someone Have Used Corona?

Corona SDK was a cross-platform engine (iOS, Android, and later Windows 8) that hid many of the low-level details of game development behind a simple Lua interface. The goal was to let developers focus on gameplay logic rather than system complexity, and in its time, this approach worked well.

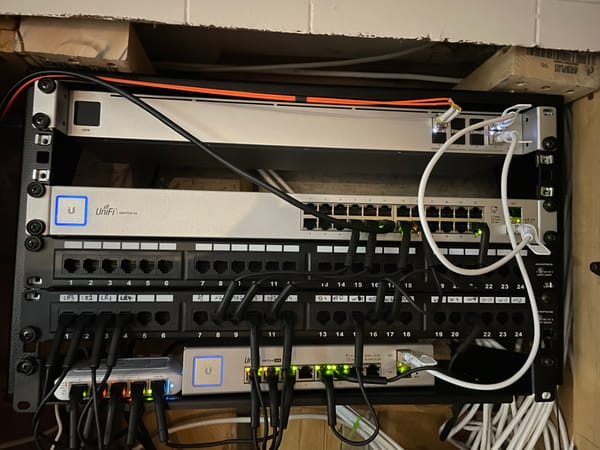

My own experiences with Corona SDK were part of a two-year journey into mobile development. Back in early 2011, I built BlokPanic to better understand the realities of iOS development for iPhone and iPad. Objective-C’s message-passing paradigm and manual memory management quickly wore thin. Although I was pleased to release the game, the overall experience was disappointing. For a simple 2D matching game, the process had been far more complicated than it should have been.

When I began work on my next project, Dungeons of Infinite Monsters, I started looking for a better toolset. Among its competitors, Corona stood out as a mature, accessible solution that balanced power and ease of use, making it a natural choice for that next step.

The Good

Using Corona SDK provided a number of benefits, including a meaningful speed-up in development through technological abstraction and fast prototyping.

Game development on mobile devices was largely done using OpenGL, a standard for drawing 3D graphics on computers. While learning the basics of OpenGL could be straightforward, mastering it was notoriously difficult. For veteran game programmers, building a rendering engine was a feasible but time-consuming task. For novice developers, it was both error-prone and overwhelming. In practice, it was a challenge that should rarely have been attempted.

Tools like Corona SDK reduced the need to build complex graphics components from scratch. They allowed novice programmers to focus on game logic while still producing polished projects. Using a mature tool like Corona also improved stability by reducing the amount of error-prone code developers had to write themselves.

function button:setText( newText )

local labelText = self.text

if ( labelText ) then

labelText:removeSelf()

self.text = nil

end

if ( params.size and type(params.size) == "number" ) then

size=params.size else size=20 end

if ( params.font ) then

font=params.font

else

font=native.systemFontBold end

if ( params.textColor ) then

textColor=params.textColor

else

textColor={ 255, 255, 255, 255 } endLua is pretty easy to learn.

Another key benefit came from Lua, the scripting language used by Corona SDK. Lua was easy to learn and allowed developers to quickly prototype gameplay elements. This rapid iteration shortened feedback cycles, enabling continuous testing and helping teams identify weak ideas early before they consumed too much development time.

The Bad

A simple computer game was always a combination of design ideas, art assets, and code. Art assets could be created in a variety of ways and stored in many different formats. Although the code was responsible for displaying or playing these assets, transforming them into a usable format for the game was known as the content pipeline.

For example, assets designed in a vector format such as Illustrator or Flash needed to be exported to bitmap formats like PNG or JPEG. Those bitmaps then required adjustments in an image editing tool such as Photoshop or GIMP, often at multiple resolutions to support a wide range of devices. These steps combined into a significant investment of time and effort.

Corona SDK simplified much of the programming required to build a game, but it offered very little to improve the content pipeline. Developers were left responsible for processing and managing all assets going into a project, from art and music to configuration files.

Lua, which was one of Corona’s greatest strengths, also became a weakness. As projects grew in complexity, Lua code could quickly become unmanageable without strict coding discipline. Larger projects often struggled under this weight.

Finally, Corona SDK lacked a formal integrated development environment (IDE). While a plug-in for Sublime Text existed, Corona Labs described it as a work in progress. Third-party tools like Lua Glider and Outlaw IDE (formerly known as Corona Project Manager) were available, but they never matched the ease of use offered by a fully integrated environment.

The Ugly

Corona’s boldest claim was that it allowed developers to build applications 10x faster than using native APIs such as OpenGL or physics libraries. To support this, the company often showcased a simple comparison: in Corona, an image could be displayed with a single line of code:

display.newImage("myImage.png")The equivalent Java example was 106 lines long, while the Objective-C version stretched to 313 lines. The argument was straightforward: fewer lines of code meant faster development. While appealing, this reasoning rested on flawed assumptions.

A closer look at the Java and Objective-C samples revealed that much of the extra code was boilerplate used to set up the display window, initialize OpenGL, and prepare the quad for rendering the image. Although verbose, this setup only needed to be written once. Once complete, rendering code made up only a small fraction of the overall project.

Even more problematic was the assumption that programming alone was the bottleneck in game development. By the 2010s, other factors—content creation, balancing gameplay, and quality assurance—often consumed more time than coding itself. Corona SDK’s marketing ignored these realities, oversimplifying the challenges of making a polished game.

At the Time

Over its first few years, Corona SDK evolved considerably, and much of that evolution was positive. One important milestone was the addition of the Storyboard scene-manager library, a feature that had been critically missing in earlier versions. At the same time, it was hard to ignore the growing emphasis on monetization libraries and the sometimes overzealous marketing that surrounded the engine.

Taking both strengths and weaknesses into account, Corona SDK remained a solid choice for building 2D games across multiple mobile platforms. Although the licensing cost could seem prohibitive, the tool often paid for itself when tied to a successful game. For developers starting a new 2D mobile project during that era, Corona SDK was a platform worth serious consideration.

The Fall and Aftermath

Corona’s momentum began to slow by the mid-2010s. Engines such as Unity expanded their mobile capabilities, while open-source projects like Cocos2d-x offered a free alternative that attracted many developers. Corona struggled to keep pace with demands for integrated editors, stronger asset pipelines, and support beyond 2D graphics.

In 2017, Corona Labs was acquired by Appodeal, an ad monetization platform. Development continued for a short time, but the focus shifted heavily toward advertising integrations. By 2020, Appodeal discontinued official support and released Corona as an open-source project under the name Solar2D.

Once open-source, Corona SDK became Solar2D

Solar2D remains available today and is maintained by a small but dedicated community. It is still viable for lightweight 2D games, yet its role in the industry is now minimal compared to Unity, and the more recent surge in interest around Godot. Most of the once-thriving Corona community has moved on, leaving Solar2D as a niche option for hobbyists and educators.

Reflection

Corona SDK’s story highlights both the opportunities and risks of rapid innovation in game development. It gave many developers a practical entry point into mobile games and helped shape how lightweight engines approached cross-platform design. Yet it also demonstrated the dangers of relying on a proprietary ecosystem that could be redirected or abandoned when business priorities changed.

Although Corona faded from the spotlight, its open-source successor Solar2D has left a mark through a different kind of legacy. Independent studios such as Kamibox produced distinctive and award-winning titles with it, including Song of Bloom (Apple Design Award, 2019) and see/saw (2018). Other games, like Gunman Taco Truck and Designer City II, also found audiences. These projects show that even after mainstream adoption declined, the engine continued to support creative work in the indie scene.

Today, Corona is best remembered as an important stepping stone in the history of mobile game development. It opened doors for countless creators during the early mobile boom and, through Solar2D, continues to quietly empower developers who value simplicity and speed over large-scale features.